Near the end of March 2020, ten days into the Bay Area’s shelter-in-place order, I reached out to Fire Monk David Zimmerman to inquire about the parallels between his experience protecting Tassajara Zen Mountain Monastery from a wildfire in 2008 and his current experience, as abiding abbot at San Francisco Zen Center’s City Center, during the coronavirus pandemic.

Here is our exchange. May it open your heart, settle your mind, and help you to remember that we’re in this (and every) conflagration together.

CMB: Is your experience during the 2008 Basin Complex Fire coming to mind now, and how are you drawing on that experience?

DZ: The Basin Complex Fire has definitely been coming to mind for me these days. I was having some major déja vu initially, especially when the three-week shelter-in-place order first went into effect. As you know, three weeks was how long it took for the fire to finally reach Tassajara. Just as we did in 2008, so now has our community quickly taken steps to protect ourselves and prepare for the possibility that the virus may eventually find its way to our doors. We’re even using some of the terminology related to fire-engagement; for example, we’ve identified the SFZC president as the “incident command”. I admire how we have together quickly responded and taken up safeguards to take care of everyone. Of course, there’s been some confusion and communication glitches, just as there were in 2008, but this is to be expected given the need for a quick turn-about and that we’ve never had to prepare for meeting a pandemic as a community before.

The main thing I want us all to realize is that we can only do our best. We make our best effort to prepare and take good care of ourselves, and then let go…let go of thinking we can control everything or every little detail, because we simply can’t. If causes and conditions are such that a wildfire or virus still makes its way into our communities and homes, then we accept that reality when it happens and turn our attention and efforts to addressing the immediate situation at hand. Ultimately we can only meet the moment that’s before us as best we can given circumstances.

CMB: What is your personal level of fear or unease, and how are you meeting it?

DZ: I’m not particularly feeling fear about COVID-19 in regard to my own well-being, in part because I don’t fall into the identified high risk category. My concern is centered on the well-being of others, and particularly my community and family. I remember feeling this way in 2008 as well in regard to the threat of wildfire and my role as Tassajara director at the time. I was less concerned about how I personally would make it through the fire as I was about how Tassajara and the other monks would fare. Of course, just as I certainly wouldn’t want to be injured by fire or have our spiritual homestead damaged, I’d rather not become ill with COVID-19, and I also don’t want to inadvertently pass the virus to others.

In both the case of meeting fire and meeting COVID-19, I think it’s important not to give into fear or panic. These emotion states undermine our capacity to clearly see the truth of the present moment. If our thinking and perspectives aren’t clouded by fear, then we’re better able to give our energy to addressing the practical details related to what’s immediately necessary rather than get ourselves overly worked up over assumptions about various scenarios of what might happen. Our ideas about the future are just that; ideas. As the Dalai Lama said, “If a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there’s no need to worry. If it can’t be solved, then worry is of no use.”

I do have some unease when I think about the potential hardships that will linger for months or longer after the pandemic has run its course, due to the major disruption of our social and economic systems. So many people are already suffering from illness or from the loss or duress of taking care of loved ones, or from having lost their livelihood due to the disruption that comes with extended periods of shelter-in-place and the closing of businesses.

CMB: In 2008, you didn’t know if or when the fire would arrive, yet you had to prepare and be ready if it did. While the work was not easy, at least it was (often) clear what needed to be done—limbing trees, building out Dharma Rain, evacuating non-essential personnel, etc. In this moment, we don’t know how coronavirus is going to change our lives in the near or far term. So much uncertainty is disorienting and hard to bear. Can you speak about how you took refuge in what’s often referred to in Zen as “don’t-know mind” as the Basin Complex fire approached, and the relevance of “don’t-know mind” now?

DZ: As you know, “don’t know mind” is a mind akin to what Suzuki Roshi called “Beginner’s Mind”, a mind free of assumptions or expectations.

Over the three weeks while we were preparing for the fire at Tassajara, I would often return to my cabin at the end of the day, both exhausted and agitated. Sometimes I would sit on the edge of my bed and process a day’s worth of new information and communications, strategizing and planning, and decision-making━ tracking the fire’s progress and discerning what it might mean…or might not…for Tassajara and for the wider SFZC community. At those times, I was keenly aware of the weight of my position as director, including that I was responsible for the safety and welfare of not only the monastery but people’s lives. And with this came the deep desire to know the outcome…to know that in the end we’d all be ok. But this wanting to know only created more distress for me. So instead, I actively embraced not knowing. I would sit on the edge of my bed and repeat over and over to myself…”I don’t know …I don’t know…I don’t know.”

Saying these words over and over, feeling the weight of their truth, was actually liberating. Liberating because they were the truest thing that could be said. I really didn’t know what the outcome would be; there really was no way to know. My only salvation was to give myself over to this truth…and let go.

I think the situation we find ourselves in now with COVID-19 is the same, really. We’re doing what we can to prepare the community, and yet we really don’t know whether and how the virus might enter our community, who will be impacted, who if anyone might die, and what the long-term impact will be. There’s so much we don’t know, although we can attempt predictions.

I don’t know…I don’t know.

Saying these words over and over, feeling the weight of their truth, was actually liberating.

Liberating because they were the truest thing that could be said.

While the virus obviously won’t destroy our buildings in the same way a fire might, the economic toll on our San Francisco Zen Center community could be such that, due to not being able to bring in the necessary revenue from our programs and donations, we might need to make some painful economic decisions in terms of people and property. There’s no insurance coverage for the impact of a virus, and unlike the 2008 fire in which SFZC was one of a number of communities directly impacted, in the case of the coronavirus a majority of the entire human population will most likely be impacted in some way.

I keep reminding myself that it’s really always like this….we really don’t know what the next moment’s going to bring. We so often fool ourselves into assuming that things will continue in a certain linear progression and that we have a general idea of what’s going to happen next. And yet, if we study our lives closely, we recognize the fallacy of this way of thinking. A fire or pandemic just serves to throw into relief this fact. Part of the shock we feel comes from realizing we’ve been fooling ourselves for so long.

CMB: In times of crisis and fear, people look for someone or something to blame. But at Tassaraja in 2008, you and others in the Zen community didn’t demonize wildfire, but rather, made efforts to harmonize with it and see our interconnection with the larger world around us, and to respect the role of fire in the wilderness. The attitude was: Fire is just fire, doing what fire does. Can you say the same of coronavirus—it is just a virus, doing what a virus does?

DZ: Yes, I think it’s fair to say that the virus is just doing what a virus does; the virus is expressing its nature of being a virus. It has no intention to do harm; it just is maintaining itself as any other organism tends to maintain itself through replication. I was curious to learn that technically the virus isn’t really a “living” thing; it’s just a series of interactions unfolding under certain favorable circumstances. When I reflect on this, I’m less likely to take the behavior of the virus personally or “demonize” it in some way.

One of the main differences with COVID-19 in comparison to wildfire is that you can see wildfire with the naked eye, so you can see when it’s coming in your direction, and you can actively and directly engage it should it come to your home. But COVID-19 is invisible without the aid of a microscope, and it can spread quietly without anyone immediately realizing what’s happening. And unlike a wildfire that you can directly engage and manage to some degree to lessen its severity and spread, once you have the COVID-19 virus, it’s a matter of letting it run its course since there’s not much medicine is able to do at the moment in terms of a cure.

My engagement with the Basin Complex fire taught me great respect for wildfire. I became very curious about how wildfire behaves and the valuable impact that it has on the wilderness. The wilderness actually depends on wildfire for its long-term health, in part because it burns away a lot of overgrowth and fertilizes the ground for new growth and possibility. I’ve similarly become curious about COVID-19 and the advent of pandemics, learning about how a virus behaves, evolves, and makes its way through human communities. Both wildfire and viruses need to be respected and recognized as natural processes; while we don’t need to demonize them, we also don’t need to welcome them into our home to wreak havoc.

Blame is never a helpful attitude as it locks into a victim mode. What is helpful is to understand the causes and conditions for how something came to be, as well as the causes and conditions for how it might pass, and then work to ensure beneficial conditions. Using curiosity and inquiry we can transform our limited views to have a deeper understanding of how things have come to be.

Some people have taken the view that the true virus is us…is human beings. I can certainly appreciate the analogy. Humanity is devouring the Earth and its resources in order to replicate itself, and in doing so we are killing the very body we depend on. Our lack of care for the Earth body has led to various forms of environmental disease or dis-ease. I don’t think it’s far-fetched to think that one of these forms of dis-ease is now expressing itself as the coronavirus disease.

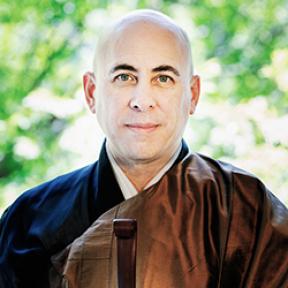

The Buddha was buried in the bocce ball court for safekeeping during the 2008 Basin Complex Fire.

Photo: Mako Voelkel.

CMB: What does “not turning away” look like in this moment when we must socially distance and self isolate, yet so many are suffering, directly and indirectly, from the virus sweeping the globe?

DZ: The idea of “not turning away” in Buddhism is ultimately about not turning away from seeing things as they truly are. It’s to see what is and do our best to keep our hearts and minds open, even if we don’t necessarily like or approve of what we see or wish things were different in some way. Of course, sometimes it’s very practical or wise to physically ‘turn away’ in order to ensure one’s safety and well-being. But ultimately not turning away is about how we’re relating to an experience. It’s about meeting whatever is before us with direct awareness and acceptance: this is what is. So now how do I want to intentionally engage it?

I prefer using “physical distancing” over “social distancing”, as I think the term social distancing can contribute to exasperating already existing social inequities and injustices. Physical distancing is done out of love…so as not to spread the virus and create the conditions for people to become infected. Physical distancing in this case is turning away from doing harm to oneself or others. It’s turning away from harming and turning toward supporting the well-being of all. It’s done with a keen awareness of our profound interconnectedness. So while we’re maintaining the recommended six feet apart from others in the street or other public places, we can also at the same time be extending to them across the physical space wishes for their safety and well-being. We can intentionally fill the space between us with friendliness and compassion.

We are fortunate to live in a time when we can reach out and stay connected to others through phone and video calls, emails, letters, etc. In times of pandemic we can stay connected while also honoring safe spacial protocols.

I’ve been suggesting to the Zen community that we consider physical distancing, shelter-in-place and other forms of protective isolation as an opportunity to do a personal monastic retreat (sesshin), in which we give ourselves the space and time to turn inward. So rather than engaging in our usual habits around socializing━and particularly the kind of socializing we do in order to avoid being with what we’re truly feeling━we take this time to turn inward to study who we are and our true nature.

CMB: Hopefully we’ll find ourselves on the “other side” of this pandemic, having learned something about ourselves and the world we inhabit. What pearls of wisdom do you hope humans extract from this harrowing moment?

DZ: First, I hope we learn to recognize and appreciate our profound interconnectedness with each other and with the world. I hope we realize that we need to do more to respect and care for our natural environment, and we need to do more to respect and care for other human beings, especially those impacted by social, economic, and environmental inequities. We can recognize that there’s the need to work toward creating better conditions for all people to be happy, healthy and prosper, and to have strong safety nets in place when major challenges such as a pandemic arise.

We’re seeing how intimately linked we are to the natural world, whether in the form of fire or viruses or global warming or climate change. We also need to do more to prepare for major calamities such as pandemics and wildfire. They have been with us since the dawn of human history, and will most likely continue to be so for centuries to come. The US had in fact a robust plan and staff in place for the likelihood of a major pandemic, but the current administration gutted it two years ago. Senator Kamala Harris recently pointed out that our ability to meet this summer’s wildfire season in California━which is already looking like it could be major due to current drought conditions━will be hampered due to both the financial and labor impact caused by meeting the pandemic.

Finally, I think this is an opportunity to do things differently. I saw a Facebook post the other day that gave some sage advice: “In the rush to return to normal, take the time to consider which parts of normal are worthy returning to.” This time of pausing and slowing down is sacred; it’s allowing us an opportunity to refocus on what’s essential and connecting in our lives. The unique situation is giving us the space to reach out and (safely) reconnect to not only friends and our loved ones, but also to reconnect to ourselves and our inner life. Inadvertently, this pause is also giving the Earth a break from our relentless polluting of it. Here’s an opportunity to let old systems that weren’t working remain defunct, and to instead come up with new and creative ways to address old problems.

It sounds cliché, but it’s true; we’re all in this together.